This blog was originally posted on EDF Voices.

Residents of New York City and other East Coast metro areas are grappling with some of the poorest air quality in those regions in more than a decade. But it’s not from traffic — it’s from a wildfire burning thousands of miles away. Oregon’s Bootleg Fire has already torched more than 340,000 acres of forests and grasslands, and its smoke is traveling across the country.

This year’s fire season, which started early due in part to record-breaking heat waves and an expansive drought, is expected to be brutal — threatening farmland, forests and grasslands throughout the western U.S. And its effects are reaching far beyond those states.

The heat from these larger fires is sending smoke, black carbon, nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons higher into the atmosphere, where they can form other harmful pollutants, such as ozone. Often, the larger fires have enough heat and upward momentum to send their plumes into the free troposphere — above the ground-level layer of air — where there are fewer removal pathways and stronger upper-level winds. This is why they can travel such long distances.

Climate change is making extreme weather worse

Wildfires like the Bootleg Fire are part of a series of extreme weather events influenced by climate change.

Because hotter air can hold more moisture, higher-than-normal temperatures pull moisture from soil and foliage. Water vapor is itself a strong heat-trapping gas, so more of it evaporating into the air raises the air temperature even higher, causing even more moisture to be pulled into the air. This is a positive feedback cycle — “positive” because it builds on itself, not because it’s good for the environment.

Typically, the atmosphere would warm and then cool, releasing moisture buildup as rain in predictable summer patterns. Instead, because the atmosphere is holding more heat, it’s holding more moisture, increasing the odds that torrential rain will then deluge communities, creating massive floods such as those seen this summer in Germany and China. Our hotter oceans also contribute to larger rain events in a similar way, by increasing moisture in the atmosphere.

How to protect yourself when air quality is poor

As hot and dry surface conditions continue across the western states, residents of other parts of the country are suffering as well. Wildfire smoke can cause significant damage to health, so people with a history of heart disease, asthma and other ailments should plan their time outdoors carefully.

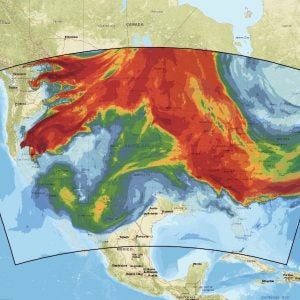

New tools can help. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has posted a national forecasting map showing both vertically integrated and near-surface smoke, enabling viewers to better predict when and where smoke will be at its worst in their area.

And the Interagency Wildland Fire Air Quality Response Program is displaying real-time air quality data from regulatory monitors and low-cost sensors deployed by individuals. It provides updated readings from air monitors across the country, as well as trend forecasts and suggestions for people who are most sensitive to air pollution.

As an outdoor enthusiast, I find new tools like these really helpful, often planning my own outside activities using the information they provide. As an air quality scientist, I am excited to see these improvements in our ability to track and trace air pollution, and I am working on related online tools that will help people understand their relationship to air pollution. As an environmentalist, I wish these tools weren’t necessary, and I am thankful to be part of an organization focused on reducing human influence on the climate.

It’s not too late to slow the pace of climate change — if we take bold action now.

Stay safe: The best way to protect your health during periods of heavy wildfire smoke is to stay indoors and keep indoor air as clean as possible by using air conditioning (on recirculate mode) or a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) purifier.

If you must spend time outdoors, an N-95 or P-100 respirator-type mask can lower your exposure to particulate matter. Further guidance on respirator masks is available from the U.S. EPA.